“In my thirty-three years by his side, I cannot remember ever being ashamed by a single bad action on his part. He was honest, without guile, innocent, infinitely sweet toward others, fierce only toward himself.” ~ Elina Kazantzakis

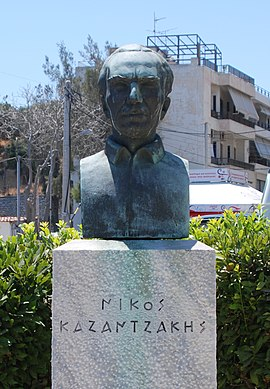

I have previously expressed my affinity for the thought of the Greek novelist Nikos Kazantzakis (1883 – 1957). I would now like to highlight a few more of his salient ideas. I begin with a disclaimer. Kazantzakis was a voluminous author who wrote a 33,333 line poem, The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel, six travel books, eight plays, twelve novels, and dozens of essays and letters. No summary does justice to the complexity of his thought. He was a giant of modern Greek literature and was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in nine different years. He is best known to the English-speaking world for his novels, Zorba the Greek and The Last Temptation of Christ, as both were adapted to the cinema.

In the prologue to Nikos Kazantzakis’ autobiography, Report to Greco, he writes that there are three kinds of souls: One wants to work; one doesn’t want to work too much, and one finds solace in being overworked. Kazantzakis thought of himself as the third type of soul.

Nikos Kazantzakis was born in 1883 in Heraklion, Greece into a peasant family surrounded by fishermen, farmers, and shepherds. His early life always remained with him,

Both of my parents circulate in my blood, the one fierce, hard, and morose, the other tender, kind, and saintly. I have carried them all my days; neither has died … My lifelong effort is to reconcile them so that the one may give me his strength, the other her tenderness; to make the discord between them, which breaks out incessantly within me, turn to harmony inside their son’s heart.

As a child, he was enrolled in a school run by French Catholics where he found religious history fascinating with its fairy tales of “serpents who talked, floods and rainbows, thefts and murders. Brother killed brother, father wanted to slaughter his only son, God intervened every two minutes and did His share of killing, people crossed the sea without wetting their feet.” Religion would become a lifelong object of his thinking.

After completing his secondary education, he sailed to Athens where he studied law for four years. He recalled the time with sadness: “My heart breaks when I bring to mind those years I spent as a university student in Athens. Though I looked, I saw nothing … this was not my road …” After he returned home he wandered the countryside, alone except for his books and notebooks. He had begun to feel the pull of writing: “Here is my road, here is duty.” He would never look back.

Indignation had overcome me in those early years. I remember that I could not bear the pyrotechnics of human existence: how life ignited for an instant, burst in the air in a myriad of color flares, then all at once vanished. Who ignited it? Who gave it such fascination and beauty, then suddenly, pitilessly, snuffed it out? “No,” I shouted, “I will not accept this, will not subscribe; I shall find some way to keep life from expiring.”

His Philosophy

In his early years Kazantzakis was moved by Nietzsche’s Dionysian (emotional and instinctive) vision of humans shaping themselves into Supermen, and with Bergson’s Apollonian (rational and logical) idea of the elan vital. From Nietzsche, he learned that by sheer force of will, humans can be free as long as they proceed without fear or hope of reward. From Bergson, under whom he studied in Paris, he came to believe that a vital evolutionary life force molds matter, potentially creating higher forms of life. Putting these ideas together, Kazantzakis declared that we find meaning in life by struggling against universal entropy, an idea he connected with God. For Kazantzakis, the word god referred to “the anti-entropic life-force that organizes elemental matter into systems that can manifest ever more subtle and advanced forms of beings and consciousness.”[i]The meaning of our lives is to find our place in the chain that links us with these undreamt of forms of life.

We all ascend together, swept up by a mysterious and invisible urge. Where are we going? No one knows. Don’t ask, mount higher! Perhaps we are going nowhere, perhaps there is no one to pay us the rewarding wages of our lives. So much the better! For thus may we conquer the last, the greatest of all temptations—that of Hope. We fight because that is how we want it … We sing even though we know that no ear exists to hear us; we toil though there is no employer to pay us our wages when night falls. [ii]

In his search for his god—or what I would call his search for meaning—he ends not as a believer, prophet, or saint, he arrives nowhere. Kazantzakis thought of the story of his life as an adventure of mind, spirit, and body—an odyssey or ascent—hence his attraction to Homer. In, The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel, Odysseus gathers his followers, builds a boat, and sails away on a final journey, eventually dying in the Antarctic. According to Kazantzakis, Odysseus doesn’t find what he’s seeking, and he doesn’t save his soul—but it doesn’t matter. Through the search itself, he is ennobled—the meaning of his life is found in the search. In the end, his Odysseus cries out, “My soul, your voyages have been your native land.”[iii]

In the prologue of Report to Greco, Kazantzakis claims that we need to go beyond both hope and despair. Both expectation of paradise and fear of hell prevent us from focusing on what is in front of us, our heart’s true homeland … the search for meaning itself. We ought to be warriors who struggle bravely to create meaning without expecting anything in return. Unafraid of the abyss, we should face it bravely and run toward it. Ultimately we find joy, in the face of tragedy, by taking full responsibility for our lives. Life is a struggle, and if in the end, it judges us we should bravely reply as Kazantzakis did:

General, the battle draws to a close and I make my report. This is where and how I fought. I fell wounded, lost heart, but did not desert. Though my teeth clattered from fear, I bound my forehead tightly with a red handkerchief to hide the blood, and ran to the assault.”[iv]

Surely that is as courageous a sentiment in response to the ordeal of human life as has been offered in world literature. It is a bold rejoinder to the awareness of the inevitable decline of our minds and bodies, as well as to the existential agonies that permeate life. It finds the meaning of life in our actions, our struggles, our battles, our roaming, our wandering, and our journeying. It appeals to nothing other than what we know and experience—and yet finds meaning and contentment there.

Kazantzakis was always controversial and misunderstood, his philosophy too ethereal for most readers. He was accused of atheism in 1939 by the Greek Orthodox Church, although he was never summoned to trial. They tried again in 1953, outraged by his depiction of Jesus in The Last Temptation of Christ—a book subsequently placed on the Index of forbidden books by the Roman Catholic Church.

In the last decade of his life Kazantzakis was prolific, producing eight books. A psychologist once told him that he possessed energy “quite beyond the normal.” In 1953 he developed leukemia, frantically throwing himself into his work, but wishing he had more time. “I feel like doing what Bergson says— going to the street corner and holding out my hand to start begging from passersby: ‘Alms, brothers! A quarter of an hour from each of you.’ Oh, for a little time, just enough to let me finish my work. Afterwards, let Charon come.” He continued to work and travel, but died in 1957 with his wife at his side.

Just outside the city walls of Heraklion Crete, one can visit Kazantzakis’ gravesite, located there as the Orthodox Church denied his being buried in a Christian cemetery. On the jagged, cracked, unpolished Cretan marble you will find no name to designate who lies there, no dates of birth or death, only an epitaph in Greek carved in the stone. It translates: “I hope for nothing. I fear nothing. I am free.”

The gravesite of Kazantzakis.

-----------------------------------------------------

[i] James Christian, Philosophy: An Introduction to the Art of Wondering, 11th ed. (Belmont CA.: Wadsworth, 2012), 656

[ii] Christian, Philosophy: An Introduction to the Art of Wondering, 656.

[iii] Christian, Philosophy: An Introduction to the Art of Wondering, 653.

[iv] Nikos Kazantzakis, Report to Greco (New York: Touchstone, 1975), 23

source:

https://reasonandmeaning.com/2021/12/31/summary-of-the-philosophy-of-nikos-kazantzakis/.